Medications for Autism

Did you know there are only two medications FDA approved for autism? If you have autism or are a parent, you may be thinking: I, or my child, have been on wayyyyy more than two medications. I know I have.

Autistics are prescribed a variety of medications, supplements, diets, therapies… the list goes on. For a medication to be for autism, it has to treat the “roots” of autism, not its affiliated disorders. The roots of autism include (1) communication deficits across multiple contexts and (2) rigid and restrictive patterns of behavior/interests. According to the DSM-5, these areas define what it means to be autistic.

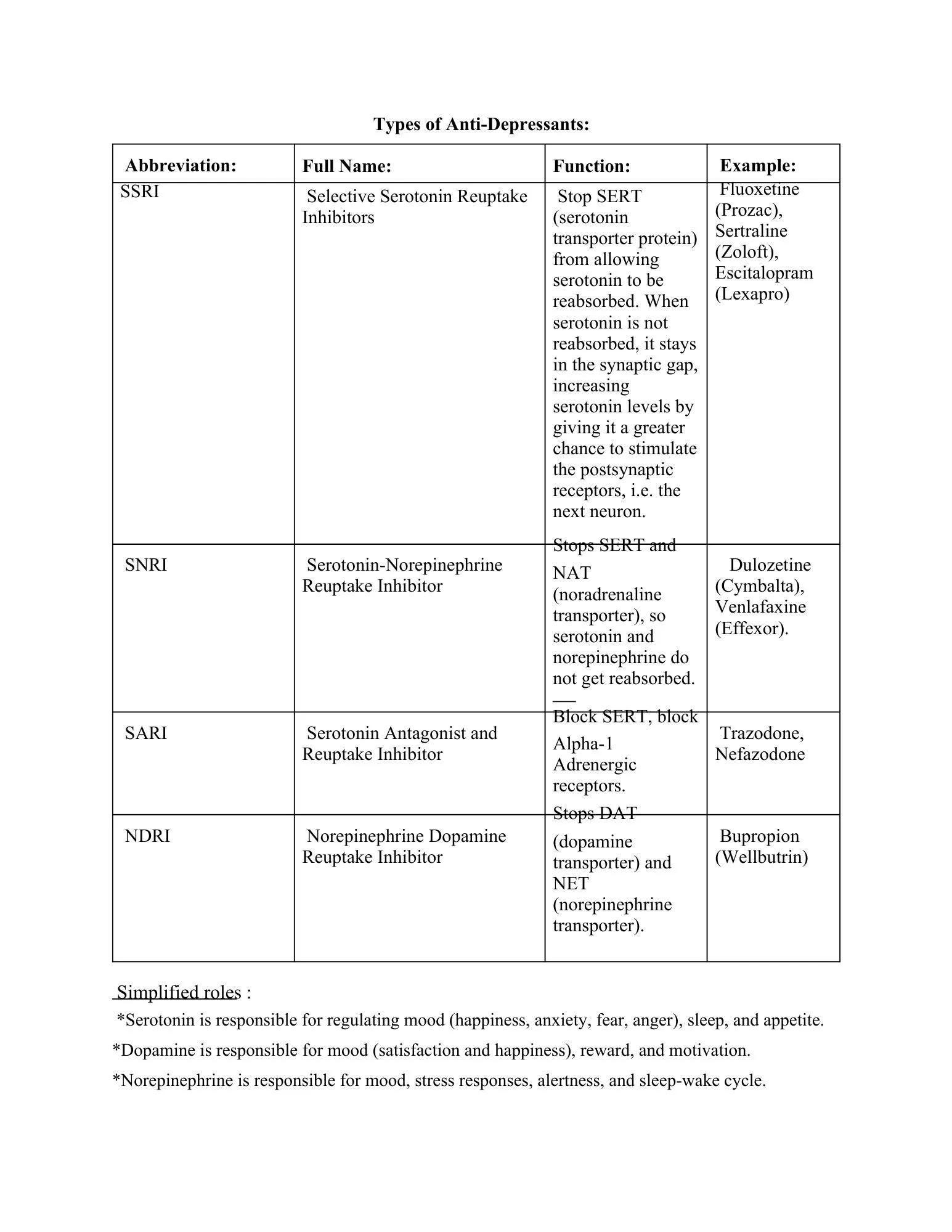

Additionally, autism is unlikely to be a stand-alone disorder. Children and adults with autism often have one or more accompanying diagnoses. These diagnoses can include epilepsy, GI disorders, ADHD/ADD, sleep disorders, and a variety of mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder. Many of these disorders have medications in ample supply, meaning they have been around and work well. For example, many children with autism are on sleeping medications including, but not limited to, hydroxyzine (an antihistamine), trazodone (an SARI), geodon (atypical antipsychotic), and clonidine (an antihypertensive). For anxiety, buspirone (an anxiolytic) and SSRIs like Prozac and Zoloft are commonly prescribed. Note: benzodiazepines (a type of anxiety medication) are largely not recommended for autistic children because of their paradoxical effects (increasing anxiety/aggression) and because of their negative cognitive effects. To treat depression, most use typical SSRIs like those mentioned above, or Wellbutrin (an NDRI). For hyperactivity, impulsivity, or aggression, Ritalin (a stimulant), Venlafaxine (an SNRI), and Adderall (an amphetamine).

Phewy! That was a lot of big words and confusing acronyms, but the truth is, most autistics are on one or several of the medications above. At first, many of us fight going on medications. It can be unnerving. There are so many options (as we just saw), and the way they work are complex and hard to grasp. They can also have some severe side effects. For all these reasons, myself and my family avoided medications for my autism, anxiety, OCD, depression, and insomnia. We wanted to take a more naturopathic approach, and tried to do so for nearly a year, but to make a long story short, I now take mental health medications; they have undoubtedly made my life better. That said, I still harbor conflicting feelings about them. I hope that I will not need them forever, despite having a relatively smooth time figuring out the best medications and doses, and only experiencing a few side effects. If I am being completely truthful, I think my “hope” to be off medications comes from deep-seated denial of wishing my autism would get better or become “less” over time.

If, or when, you take the leap to medication, there are so many options. Make sure you use a trusted healthcare provider, and make sure you do your research. As far as medications for autism go, I do not recommend going with your pediatrician unless they specialize in autism and other subsequent mental health issues. See a specialist; find a psychiatrist, neurologist, specialized PA, or the like.

In the beginning of this blog, I mentioned the FDA has only approved two drugs for autism. So far, all the medications I’ve mentioned treat co-occurring disorders, not autism itself. That said, the two medications FDA approved for autism are both antipsychotics. They are risperidone (Risperdal) and aripiprazole (Abilify). Both are atypical antipsychotics, meaning they work on serotonin and dopamine receptors. Risperidone is a second-generation antipsychotic while Aripiprazole is a third-generation antipsychotic. The difference is that Aripiprazole is a partial agonist, so it partially blocks receptors. When dopamine receptors are fully blocked, side effects are more prevalent, so Aripiprazole often has less side effects than Risperidone.

- - -

Disclaimer: the medications I discuss today are much more complex than what we will explore in this blog. I am not a doctor or specialist, and I do not want to run the risk of spreading incorrect information. Research, and talk to your physician(s) for further details.

- - -

Why are antipsychotics the only medications approved for autism? Because they treat behaviors. Saying “behaviors” immediately carries a negative connotation, but we have to be honest with ourselves: autistics have a lot of behaviors and many are not good for them or those around them. Risperidone is prescribed for irritability and aggression and Aripiprazole for irritability. Risperidone has been proven to drastically improve explosive behaviors and aggression, including self-injury, and it decreased hyperactivity. There is a serious downside to Risperidone though, its side effects. Children on Risperidone are likely to gain weight due to an increased appetite caused by the medication. Research from Shea et al (2004) and McCracken et al (2002) claim that within 8 weeks, children taking Risperidone gain 6 pounds on average. Other side effects include drowsiness, hyperprolactinemia, and involuntary movements. Aripiprazole has fewer side effects and a faster onset. Like Risperidone, studies show that Aripiprazole works mainly for children/adolescents to improve irritability, hyperactivity, and in some cases, lessened stimming (Hirsch & Pringsheim, 2016, p. 2).

Despite being approved for autism, even these medications do not do what many of us would hope. When I hear “medication for autism,” I want it to be a magic solution which would take away my black-and-white thinking, cure my communicative deficits, and make my brain more flexible, but alas, these medications are not magic potions. In fact, the FDA’s use of “approved for autism” is misleading. When I heard there were medications approved for autism, I got excited, hopeful. Upon researching, I learned that these medications are not for autism; they do not treat the roots of autism. They are for behaviors. The closest they come to treating autism is by treating stimming, which they have shown a mediocre ability to limit. Technically, you could call this “treating repetitiveness” (a root of autism), however, I would not credit them so. Treating stimming brings even more complex questions to mind, for stimming is often an expression of a sensory need or is a communicative link to one’s emotional state. To treat stimming would mean treating the central nervous system dysfunction that causes the autistic’s need to stim, as well as eliminating any emotional/mental need to stim.

To those of you who felt a similar glimmer of excitement or hopefulness at the beginning of this blog, I apologize. Autism is still a complex mystery. Even now, in early 2026, there are no medications I would consider for autism. Here is what we do have: medications that work for co-occurring conditions. Conditions that we often label as under the “autism umbrella.” I cannot understate the value of these medications. They are life-changing for those who struggle with a myriad of disorders on top of autism, and truthfully, this includes most of us.

Mosner et al (2019) studied the prevalence of co-occurring disorders throughout autism and found that “between 70% to 95% of children and adolescents with ASD have at least one co-occurring psychiatric disorder (Gjevik, Eldevik, Fjaeran-Granum, & Sponheim, 2011; Joshi et al., 2010; Leyfer et al., 2006; Simonoff et al., 2008), 41% to 60%...have two or more co-occurring disorders (Di Martino et al., 2017; Simonoff et al., 2008), [and] between 73%-81% of adults…meet criteria for at least one current co-occurring psychiatric disorder (Buck et al., 2014; Hofvander et al., 2009; Joshi et al., 2013; Vohra, Madhavan, & Sambamoorthi, 2016).

Medications that help us with anxiety, depression, compulsions, sleep, impulsivity, focus, or irritability drastically improve our lives. They increase our energy, help us feel more joy, lessen our stress, encourage us to get out there, let us sleep peacefully and restoratively, and help us spend more time with people, or doing our hobbies and pursuing our passions.

I do not want to come off as though I am suggesting that every autistic should be on mental health medications: not everyone needs them. My favor towards medications stems from my own personal experiences, and from hearing the experiences of other autistics and of parents. I cannot imagine where I would be today if I did not get my anxiety, insomnia, and depression under control. If you could feel the strength of autistic anxiety, you would understand how unbearable it is. Plus, when you do not sleep (insomnia) everything is exacerbated, from your autistic symptoms, to your anxiety, OCD, depression, ADD, ODD, PDA, seizures, or whatever is applicable in your scenario.

While this blog has not been all too encouraging, I hope I have brought some awareness to the medications used to treat autism’s co-occurring disorders. I mostly threw out names, but there is not much else I can do, for everyone’s situation and autism is unique. The ball is now in your court; research and talk to your trusted professional to find out what would be best for your child or you. It can be daunting to start taking these medications, and it begins largely with trial and error. While the initial step is hard, nervewracking, or confusing, I want to encourage you. These medications are the difference between health and illness, happiness and sadness, and comfort and distress for many of us with autism. With trusted providers, a support system, and some networking, tackling medications becomes easy. I cannot understate the value of talking to autistics and parents and hearing their stories. You are not alone in this. To offer some help, I have attached a chart below detailing 4 classes of antidepressants.

Written on November 29th, 2025.

References

Hirsch, L. E., & Pringsheim, T. (2016). Aripiprazole for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2016(6), CD009043. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009043.pub3

McCracken et al. (2002) N. Eng. J. Med. 347, 314-321. PubMed

Mosner, M. G., Kinard, J. L., Shah, J. S., McWeeny, S., Greene, R. K., Lowery, S. C., Mazefsky, C. A., & Dichter, G. S. (2019). Rates of Co-occurring Psychiatric Disorders in Autism Spectrum Disorder Using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 49(9), 3819–3832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04090-1

Shea et al. (2004). Pediatrics 114, e634-64. PubMed